What the heck, does Heck Cattle have to do with environmentalism? Or rewilding? And is it amoral to resurrect such animals?

In a recent article, the position is outlined that rewilding is closely related to traditional nature restoration and, hence, just another form of human domination of nature. An anthropological analysis of this thinking shows how it is fundamentally mistaken.

In the 1920s and 1930s, an attempt was made to resurrect the aurochs (Bos primigenius primigenius), the extinct wild ancestor of contemporary domestic cattle. The back-bred species produced was called the ‘Heck Cattle, named after the two brothers who carried out the project.

Since the aurochs at that point had been considered extinct since the 17th century and modern genetics science had not yet appeared on the scene, the animals were recreated by a clumsy and, in fact, just aesthetically inspired form of backbreeding involving Spanish Fighter bulls. Most of the animals died during the war. However, after WW2, the work continued to breed on a few remaining animals in München, and today Heck Cattle are used as part of eco-restoration projects in numerous places in Europe. Over 2000 animals live in Europe, of which 600 roam the infamous Oostvaardersplassen.

In a new article, the philosopher Eric Katz argues that the attempt to create the Heck cattle as a form of resurrected aurochs and their subsequent use in rewilding projects (as in the Oostvaardersplassen in the Netherlands) is a prime example of the ongoing human project of the domination of nature characterising the Anthropocene.

The Heck Cattle as Nazi Symbol

Eric Katz is known for his arduous fight for the natural world to be respected in its right. However, he is perhaps better known for his work to uncover the character of the first national environmental preservation policies in the 20th century forged in the crucible of the fascist and genocidal regime of Nazi Germany. Therin, the backbred aurochs came to play a symbolic role. Although the project began in the 20s and reflected the standard search for “national” cattle and “horses” in the romantic quest for the “homeland”, it was heavily promoted as part of the resurrection of the Early Medieval Germanic Empire. The dream was to fill the extensive “primaeval” forests of Eastern Germany with megafauna enacting, playing the role of prey in reenacting the glorious past of the German race and its future supremacy.

Undoubtedly, the German preoccupation with racial thinking played a part in this preoccupation with the eugenic endeavour to backbreed the Aurochs. Also, the idea that nature might be cleansed of its later impurities by returning to a more pristine and purer state of affairs does act like a vivid and dire remembrance of the Holocaust.

According to Eric Katz, however, the story of the Heck Cattle has a wider resonance in the Nazi form of landscape planning, which they sought to “Germanize”. In this project, the architect Alwin Seifert and the railway engineer Fritz Todt led the way to resurrect the “Heimat”, a somewhat untranslatable word with its very material and tangential connotations referring to the German peasant, his family, his farm, his village and his landscape – in short, his “Lebensraum”. In this crucible, the idea of history, geography, and ethnicity blended with the concept of the healthy and balanced life of the proper German. Thus, the idea was not just to restore the native flora and fauna but also remove the “degenerate” – we would say “invasive” – species. The result was the idea of a “Racialised Landscape” as opposed to the “Romantic Landscape” of the 19th century. In this racialised landscape, the Nazis dreamt of dark forests once again teeming with aurochs, bison, wolves and eagles, all animals which were recruited to enact the myth in the best manner of Roland Barthes.

The Oostvaardersplassen and Rewilding

Based on this idea of the “Racialised Landscape” filled with “potent and wild symbols”, Eric Katz uses the history of the first European rewilding project of the “The Oostvaardersplassen” to argue his point. The Dutch biologist Franz Vera’s creation was set at 60km2 or 6000 ha; the aim was to recreate an independent and autonomous ecosystem by releasing wild horses, wild cattle, and red deer into the nature reserve and leaving it to its own devices. As is well known, the project has been a success insofar as it did succeed in creating a biodiverse and lively nature reserve of marshland and grassland. However, the initial cruelty involved in fencing the area and letting the megafauna die of “natural” starvation and illnesses without letting the animals leave the reservation turned the place into a political, ethical, and social battleground. The early photos still reverberate on the internet and gave “rewilding” a seriously bad press. Due to the presence of the Heck Cattle and its ignominious connotations as “Nazi Cattle”, the Oostvaardersplassen has occasionally been likened to a Concentration Camp on Facebook.

The point Katz wishes to make, however, reaches further. In short, He claims that “Rewilding projects do not so much re-create a ‘wild’ nature free from human intervention and activity”. Rewilding is just another form of the human management of natural processes to achieve anthropocentric goals, he writes. He argues “that policies of rewilding have historical antecedents (and parallels in philosophical meaning) to the Nazi plans for re-creating an authentic Aryan landscape in the lands of Eastern Europe. The case history of the Heck cattle projects illustrates the danger of pursuing radical forms of management of the natural world.”

But does this argument hold, we may ask? Is it fair to judge a Dutch nature restoration scheme, which has served as a pilot project for the rewilding movement, just because it chose to use Heck cattle instead of the belted Galloways, which are now the primary breed used in extensive grazing and rewilding projects?

Does the use of Heck Cattle at Oostvaarder necessarily have to taint the general idea of rewilding as it is practised with joy, pleasure, and love elsewhere?

Rewilding? What is it?

To answer this question, Katz recounts the outline of the debate between different leading scientists and practitioners on how to understand rewilding, where the main element is forsaking (traditional) ecological restoration to further self-sustaining ecosystems devoid of human interference of any sort. Thus, the main difference is lodged in a different set of values considering the role of human management – on one hand, painstaking caring and, on the other hand, turning our backs to the rewilded enclave. However, Katz chooses to see these two positions as orientation points on a continuum where total abandonment is impossible. He rejects this distinction between the two approaches to nature, pointing out that none takes out “the imposition of human intentionality on natural ecosystems”. Both approaches are “infused with human purpose”.

Ktz wishes to make the point that we cannot escape the mortal sin of intervention, inscribed in our genes as human beings. “Thus, the fundamental philosophical issue in an understanding of rewilding is the role of this human management and control, for it is an ever-present reality in the re-created”, he writes. Whether we wish for it or not, the result is hybrid landscapes. Following this, Katz points out (quoting Drenthen 2018) that “There is no escaping from history: all rewilding landscapes are layered cultural landscapes”.

A cultural and political question?

This leads to Katz’s conclusion, which claims that any “rewilding” project represents a form of “cultural politics” just as classical well-ordered restoration policies do. And in the end, any light-handed management of a particular human intervention might lead to a situation that limits the autonomy of the people who formerly lived on and off the land. Even if the wish to culturally dominate both animals, landscapes, and human races might hopefully never again reach the apogee of Nazi thinking, it does harbour the germs and spores. “But affirming the obvious fact that contemporary rewilding projects are not based on Nazi ideology or anti-Semitism does not remove rewilding in general from the overall process of human management, control and domination of nature”, Katz writes and concludes: “Rewilding is a policy that seeks the conscious transformation of the natural world into a human and culturally determined landscape. Rewilding does not restore nature or re-create a wild and spontaneous natural system. Rather, the acceptance of rewilding as a valid environmental policy acknowledges that nature and natural landscapes no longer exist and that the entire world is an artefact produced by human management and control”.

How to counter this argument?

How should we engage with Katz’s arguments? One way is to do a “cultural” and “anthropological” analysis of the formulation in this final conclusion. The point becomes to review Katz’s and others’ position on rewilding as an expression of a cultural stance rather than a philosophical set of arguments.

“No longer exist”, he writes, positing the idea that once upon a time, authentic nature and natural landscapes did, in fact, exist, whether in Paradise or the Pleistocene. Thus, whichever way he looks, he seems unable to escape the idea that once we did not exist as human beings but were just animals incapable of reflection and narration. At some point, however, we metaphorically speaking “ate from the apple” and were kicked out of this pulsating and perfect ecosystem to try and come to terms with our potential to interfere. Which he correctly points out, we have been doing ever since we shed the ape skin of our forefathers.

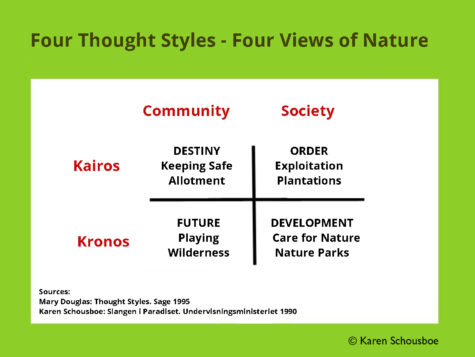

The interesting point to make here, however, is that Katz’s form of thinking, as viewed by anthropologists, may be considered just one of four different cultural or political takes on how to deal with nature, which, from an anthropological point of perspective, may be considered of as “Thought Styles” (presented best in Douglas 1995). Originally, these “Thought Styles”, as argued by Douglas, were characterised structurally through the organisation of their corresponding social landscapes. However, later anthropological thinking (Schousboe 1990) demonstrated the advantage of looking upon them as not just thought styles organising sociality but also thought styles structured temporally – with the position of Katz’s representing the narrative nostalgia of the ultimate modern “restorer” as opposed to the future-oriented constant moving and pulsating post-modern “creator” busy recruiting co-creators – in the rewilding connection the countless myriad living beings inhabiting nature.

In this sense, rewilding represents not just a method of nature restoration representing the usual interventionist activities of the social engineer dreaming of the authentic past lost forever, but rather the fun and play involved in letting loose to see what happens in the time to come.

Granted, from a formal philosophical point of view, both positions (indeed all four) may be deemed interventionists. However, to judge them ethically, we need to see them as differentiated as to their outcome. What type of nature view is best to preserve Gaia for future generations, is the question we might ask? As opposed to the alternative: Which nature view allows for the free flourishing of people and peoples to the detriment of the wilder world?

While one (Katz’s) is hopelessly caught up in the traumatic loss of the aurochs and the nostalgia for the time before 1627, when the last living specimen was allegedly lost, the rewilding position notices the fact that studies of aDNA unambiguously show that aurochs and domesticated cattle mixed and matched up through history. And yes, backbreeding by the Heck-brothers was part of a deplorable fascist enterprise creating a more pure and “Germanic” world. However, the modern-day Tauros project supported by Rewilding Europe is part of quite another venture focusing on releasing the joy of playing around by reimagining a more pulsating, vibrant world filled with the ongoing creation of the future.

Karen Schousboe

SOURCES:

What the Heck Cattle Have to Do with Environmentalism: Rewilding and the Continuous Project of the Human Management of Nature

Eric Katz

In: Ethics, Policy & Environment

Online 13 June 2023

Rewilding in layered landscapes as a challenge to place identity.

By M Drenthen

Environmental Values (2018) Vol 27 No 4, pp 405–425.

Thought Styles: Critical Essays on Good Taste

by Mary Douglas (Author)

Sage 1995

Slangen i paradiset : unges holdninger til fremtiden

By Karen Schousboe

Undervisningsministeriet 1990